Anatomy and Function of the Male Pelvic Floor

Anatomy Overview

The pelvic "floor" is an appropriate name. It is situated at the bottom of the pelvis, lies in a roughly horizontal orientation, and closes off the opening that would otherwise allow the pelvic and abdominal contents above it to fall through. It is unique in that it is the only horizontal load-bearing muscle group in the body.

Its boundaries are the pubic bone in the front (just above the genitals), the coccyx (tail bone) and sacrum in the back, and the ischial tuberosities on each side - the two bones you sit on. It has two openings in men: one to allow the urethra to pass through on its way from the bladder to the penis and the other at the anus. A useful way to visualize these muscles is to think of them as a hammock, sling, or a shallow bowl. The perineum is a specific part of the pelvic floor and is situated between the anus and genitals.

"A straight up anatomy question has come up and I don't know anyone better than you, and I certainly trust your judgement rather than my ability to figure this out on my own." - M. G.

The pelvic floor consists of two types of muscle tissue: slow twitch (Type I), which make up about two-thirds of its muscle fibers, and fast twitch (Type II), accounting for the remaining one-third. Slow twitch fibers maintain a constant tone in these muscles so that the organs above them are supported and closure is maintained in the urethral and anal openings. Fast twitch on the other hand are engaged during strong, quick contractions such as those required for intense exertion, at the end of voiding, or during ejaculation.

The pelvic floor also has an extensive array of connective tissues and is richly endowed with blood vessels and nerves, making it capable of experiencing, and creating, a wide range of sensation from pleasure to pain.

Function Overview

The functions of the pelvic floor are numerous. Among them are:

- It makes a fundamental contribution to movement and stability, and functions in coordination with the abdominal, back, and hip muscles - otherwise known as your core. Especially important is its relationship to the transversus abdominis (the deepest layer of the abdominal muscles), and the multifidus muscles in the low back. This relationship maintains the integrity of pelvic, sacral, and spinal joints during movement.

- It supports the organs directly above it: prostate, bladder, rectum, and seminal vesicles.

- It regulates continence, opening and closing the urethra and anus as needed.

- It plays an essential role in sexual function. A strong, supple pelvic floor enhances sexual response, improves performance, and heightens our sense of pleasure.

- It acts reciprocally with the respiratory diaphragm in breathing.

- It is a strong flexor of the coccyx (tail bone), bringing this bone forward when it contracts.

- The pelvic floor is the center of gravity in your frame, the place where movement is initiated, and is essential to your overall sense of well-being.

- In many Eastern traditions, this is where your life-force energy resides and is a seat of spiritual as well as physical vitality. See my Emotional and Energetic Aspects page for more on this.

For further information on male pelvic floor anatomy and function, including graphics, see below. Also see my Massage and Bodywork page for a more detailed discussion. There are "back to top" links on the right side at the end of most sections. Back to top

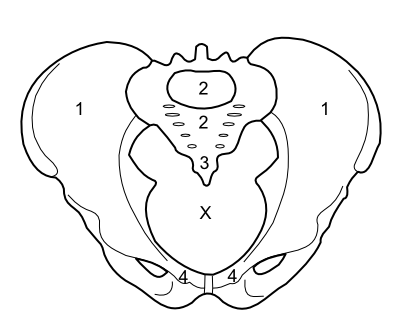

Figure 1: The bones of the pelvis and sacrum viewed from above, showing the pelvic outlet.

- 1. The paired Ilium bones of the pelvis

- 2. The Sacrum at the base of the spine

- 3. The Coccyx or tail bone at the bottom of the sacrum

- 4. The paired Pubic bones in the front of the pelvis

The X in the center marks the opening at the bottom of the pelvis called the pelvic outlet, which is spanned by the pelvic floor muscles (see Figures 2-5).

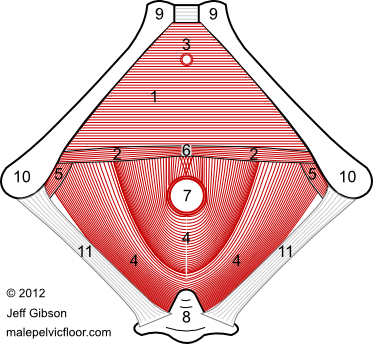

The Pelvic Diaphragm

The deepest and most extensive layer of the pelvic floor muscles is found in what is called the pelvic diaphragm (Figure 2). These muscles as a group span the entire lower opening of the pelvis (the pelvic outlet), and consist of the puborectalis, pubococcygeus, iliococcygeus and coccygeus muscles. The first three are collectively called the levator ani, and they lift the pelvic floor upward (and slightly forward) when they contract. The latter three function together as strong flexors of the coccyx, pulling this "tail bone" forward. There are 2 openings that allow passage through the pelvic floor: the urethra in front of the perineum, and the anus behind it. The pelvic diaphragm assists the sphincters in their action as gate keepers to regulate the functions of these two openings. This layer, coupled with extensive connective tissues, also provides the primary support to the organs resting above it: the prostate, bladder, rectum, and seminal vesicles. It contributes to stability and movement, particularly through coordinated contractions with the transversus abdominis in the abdomen and multifidus muscles along the spine (key parts of your core). Finally, it plays a role in respiration, posture, and sexual function.Back to top

Figure 2: The pelvic diaphragm viewed from above.

- 1. Puborectalis muscle

- 2. Pubococcygeus muscle

- 3. Iliococcygeus muscle

- 4. Coccygeus muscle

- Other muscles

- 5. Piriformis

- 6. Obturator Internus

- Other landmarks

- 7. Urethral opening

- 8. Anal opening

- 9. The paired pubic bones in the front of the pelvis

- 10. The sacrum

- 11. Coccyx (tail bone)

- 12. Tendinous arch

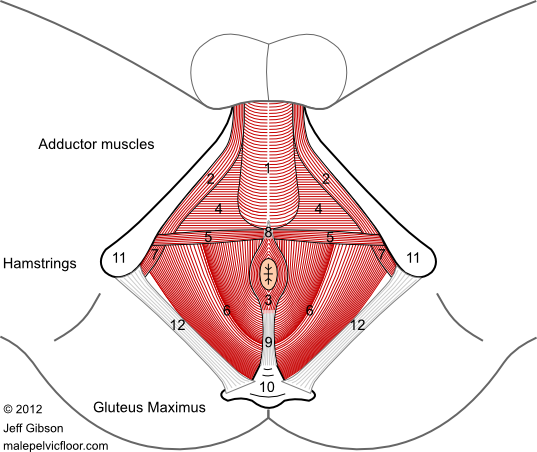

The Urogenital Diaphragm

Below and covering the front half of the pelvic diaphragm is a layer of muscles called the urogenital diaphragm - the superficial and deep transverse perineals (Figure 3). These muscles, along with their dense fascias (connective tissues), can be felt as a shelf beginning in the perineum and running forward to the pubic bone. The side-to-side direction of these fibers is in contrast to the general front-to-back orientation of the muscles of the layer above - the pelvic diaphragm. These muscles help support the pelvic floor and fix the perineal body in the midline. The perineal body consists of tendinous connective tissue and is an important central anchor point for several muscles of the pelvic floor.Back to top

Figure 3: The urogenital diaphragm viewed from below.

- 1. Deep Transverse Perineal muscle

- 2. Superficial Transverse Perineal muscles (paired)

- 3. Urinary Sphincter

- Other landmarks

- 4. Pelvic Diaphragm / Levator Ani muscles

- 5. Obturator Internus

- 6. Perineal Body (central anchor point)

- 7. Anal opening

- 8. Sacrum and Coccyx (tail bone)

- 9. Pubic bones in the front of the pelvis

- 10. Ischial tuberosities of the pelvis - the bones you sit on

- 11. Sacrotuberous Ligament

The Bulbospongiosus and Ischiocavernosus muscles

The next, and most superficial, layer is also positioned in the front part of the pelvic floor: the bulbospongiosus and ischiocavernosus muscles (Figure 4). The central bulbospongiosus encircles the bulb, or root, of the penis and connects it to the perineal body, while the ischiocavernosus surrounds the penile lateral roots, which angle like guy-wires out to the sits bones (ischial tuberosities). Both of these muscles help anchor and stabilize the penis and, via their role in compressing veins and tensioning the penile connective tissue, contribute to the initiation and maintenance of erections. The bulbospongiosus also helps empty the urethra at the end of urination, and expels semen during ejaculation.Back to top

Figure 4: The Bulbospongiosus, Ischio-

cavernosus, and Anal Sphincter muscles

- 1. Bulbospongiosus

- 2. Ischiocavernosus

- 3. Anal sphincter

- Other muscles

- 4. Deep Transverse Perineal

- 5. Superficial Transverse Perineals

- 6. Pelvic diaphragm / Levator Ani muscles

- 7. Obturator Internus

- Other structures

- 8. Perineal body (central anchor point)

- 9. Ano-coccygeal ligament

- 10. Sacrum and coccyx (tail bone)

- 11. Ischial tuberosities (sit bones)

- 12. Sacrotuberous ligament

The Sphincters

The sphincters regulate the opening and closing of the two orifices of the pelvic floor: the anus and the urethra (Figures 3, 4, and 5). The sphincter ani of the anus is comprised of an internus and externus, divided into 4 layers or rings. The internus is the inner-most ring, and is not under voluntary control. The externus has three layers: deep, superficial, and subcutaneous (below the skin), all of which are under voluntary control. Rather than being separate structures, there are significant connections between the anal sphincters and the muscles of the pelvic diaphragm, the perineal body, and the ano-coccygeal ligament (see Figure 4).

The urinary sphincters, or sphincter urethrae, also have an internal and external component. The internal sphincter is located at the bottom of the bladder just above the prostate, and is involuntary - that is, not under conscious control. The external sphincter, sometimes called the rhabdosphincter, is formed from fibers of the deep transverse perineal muscle, which surround the urethra in the urogenital diaphragm below the prostate. This is under voluntary control (see Figures 3 and 5).Back to top

The Obturator Internus and Piriformis muscles

There are two muscles on the inside of the pelvis that help form the sides of the bowl-shaped pelvic floor: the obturator internus and the piriformis (see Figure 2). These exit the pelvic bowl to attach at the top of the thigh bone (femur) and are considered muscles of the hip in a movement sense, but they have relevance to the pelvic floor both in terms of placement and in pain referral.

Nerves

Of the various nerves essential to pelvic floor function, the pudendal nerve is most worth noting. This nerve originates from sacral roots and innervates much of the pelvic floor, including the levator ani, superficial and deep transverse perineals, bulbospongiosus, external anal sphincter, and urethral sphincter. Large portions of the urogenital and anal regions receive their sensory supply from the cutaneous branches of this nerve.

Connective Tissues

Critical to the structure and function of the pelvic floor are the connective tissues: tendons, ligaments, and fascias. They encompass, suspend, anchor, and connect the bones, muscles, organs, nerves, and blood vessels of the pelvic floor - and have continuity with the adjacent thighs, low back, and abdomen. As the saying goes, it really is all connected.

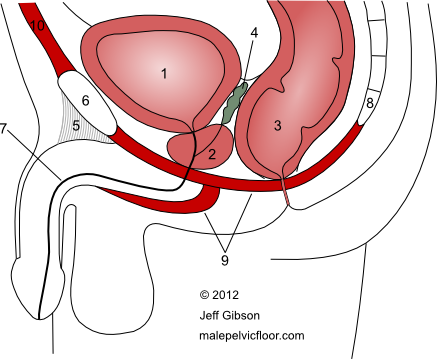

Organs Supported by the Pelvic Floor

The organs situated directly above the pelvic floor are the prostate, bladder, rectum, and seminal vesicles (Figure 5) - all of which can be adversely affected by pelvic floor dysfunction . The bladder is a storage vessel for urine, while the rectum is the last section of the large intestine. The prostate and seminal vesicles are glands that contribute fluids to sperm coming from the testicles to form semen.Back to top

Figure 5: Cross section through the midline showing the organs above the pelvic floor muscles

- Organs

- 1. Bladder

- 2. Prostate

- 3. Rectum

- 4. Seminal Vesicles

- Other structures

- 5. Suspensory ligament

- 6. Pubic bone

- 7. Urethra

- 8. Coccyx (tail bone)

- 9. Pelvic floor muscles (schematic)

- 10. Abdominal muscles above the pubic bone

External Muscles Relevant to the Pelvic Floor

There are several muscles completely outside the pelvic floor that also have functional relevance. Some fibers of the gluteus maximus attach directly to the sides and back of the coccyx and resist the pull (flexion) of the coccygeal pelvic floor muscles mentioned above. On the inside of the thigh is the adductor muscle group (adductor longus, adductor brevis, adductor magnus, gracilis, and pectineus), which often tightens reflexively when the pelvic floor does (and vice-versa) - for stability purposes, in response to anxiety and fear, or when you resist a strong urge to urinate or defecate. The same applies to the muscles of the lower abdomen (rectus abdominis, external oblique, internal oblique, and transversus abdominis). The transversus abdominis functions together with the multifidus in the low back and the pelvic floor muscles to stabilize the core during movement and protect the spine from injury. Note that some of these muscles can refer pain to the pelvis and genitals.

→ For more on male pelvic floor anatomy and function, see the Male Pelvic Floor page on my related website: coremassage4men.com.