Urinary Dysfunction and the Male Pelvic Floor

Summary

Many men experience lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) in association with Chronic Prostatitis / Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome (CP/CPPS), or prostate conditions such as Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (prostate enlargement). Many others experience urinary symptoms independent of any specific diagnosis. These symptoms can include pain, irritation, urgency frequency, hesitancy, slow stream, or dribbling.

The muscles of the pelvic floor can produce urinary symptoms as a consequence of excess tension, weakness, or other dysfunction. Additionally, pain or other sensation can be referred to the urogenital system by hyper-irritable trigger points in these muscles. Surprisingly, the muscles of the lower abdomen, often overlooked, can also cause or contribute to urinary dysfunction via the same mechanisms.

Massage and bodywork applied in a skilled manner to the pelvic floor and abdomen, as well as pelvic floor exercises where appropriate, can improve or resolve urinary symptoms when these muscles are the primary factors triggering the dysfunction.

Below you will find a short Definition of Terms ♦ a section on CP / CPPS and Urinary Symptoms ♦ The Role of the Pelvic Floor Muscles including the three mechanisms by which these muscles can adversely affect urinary function ♦ The Role of the Abdominal Muscles which are often overlooked ♦ and sections on four specific topics: Post-Micturition Dribble (PMD) ♦ Post-Radical Prostatectomy ♦ Transurethral Resection of the Prostate (TURP) ♦ and Climacturia. Rationales for massage and bodywork and / or exercise are presented throughout.

Hover your cursor over citation numbers to view the source in a pop-up text box or scroll to the bottom of the page for the full list. At the end of each section on the right side you will see "back to top" links to return to the main menu.

Definition of Terms

The term LUTS refers to Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms and encompasses a variety of symptoms and conditions, some of which you will encounter in the remarks quoted in the text below. With that in mind, here is a short glossary of terms:

Dysuria: difficult or painful urination.

Urgency: the sudden, compelling urge to urinate.

Frequency: the need to urinate more frequently than normal, without an increase in the total daily volume of urine.

Nocturia: night time frequency.

Hesitancy: a decrease in the force of the stream of urine, often with difficulty in starting the flow.

Stress urinary incontinence: the involuntary loss of urine with physical exertion such as lifting a heavy object, coughing, sneezing, laughing, or intense exercise.

Climacturia: urine leakage during orgasm, a common problem after radical prostatectomy (removal of the prostate).

Micturition: urination.

Post-Micturition Dribble: an involuntary loss of urine immediately after urinating, usually after leaving the toilet.

CP / CPPS and Urinary Symptoms

Urinary symptoms are common among those with CP/CPPS. "Irritative voiding symptoms such as dysuria, frequency, and urgency are likely to be reported by patients." write Nguyen and Shoskes [1]. Potts, in the same publication, expands on this: "Many patients experience concomitant [accompanying] lower urinary tract symptoms such as urinary urgency, frequency with or without burning, or dysuria. They may notice hesitancy or difficulty initiating a stream or an overall weakening of the stream. Still others may be disturbed by nocturia, which disrupts sleep and further exacerbates anxiety levels in these patients."

Anderson et al. assert that muscular tension associated with CP/CPPS may be responsible for urinary symptoms. "We believe that pelvic pain exists as a neuromuscular disorder, and abnormal smooth and striated muscular tension may cause pain, abnormal voiding, and sexual dysfunction." [2]. Wei He and colleagues in 2010 looked at urinary frequency, urgency, and voiding difficulties in men with Chronic Prostatitis and concluded that "Many symptoms [of disfunctional voiding] arise from pelvic floor dysfunction rather than other causes." [3]. Weiss, in an important 2001 study, states that "It is well established that dysfunctional pelvic floor muscles contribute significantly to the symptoms of intestitial cystitis [inflammation of the bladder] and the so-called urethral syndrome, that is urgency-frequency with or without chronic pelvic pain." [4].Back to top

The Role of the Pelvic Floor Muscles

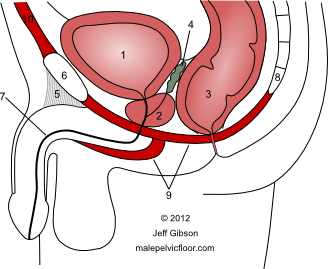

The bladder (1), prostate gland (2), urethra (7), and a schematic of the pelvic floor muscles (9). The internal urinary sphincter is located at the base of the bladder just above the prostate. The external urinary sphincter is embedded within the pelvic floor muscles just below the prostate. See my Anatomy page for a larger size and full labeling.

The muscles of the pelvic floor can contribute to voiding dysfunction via three mechanisms:

1. Excessive tension. Chronic tension and the inability to fully relax can compromise urine flow by constricting the urinary sphincters and perpetuating tightness in the supporting pelvic floor muscles, which assist the sphincters in maintaining closure. A weak stream or slow start can result. This tension can also alter the signals associated with the perceived need to urinate and the timing of doing so. "Insufficient relaxation of the pelvic floor results in hesitancy, intermittency, and high post void residuals" [11].

Massage and bodywork will help you relax your pelvic floor muscles and re-establish normal tone and function. Becoming aware of your tension and learning to relax these muscles is the first step in gaining greater voluntary control.

2. Weakness. Pelvic floor weakness is directly associated with urinary incontinence. These muscles provide the closure mechanism to prevent involuntary loss of urine, and weakness can result in dribbling or leakage (see the section on post-micturition dribble below). Continence issues can occur at any age and for several reasons but are strongly associated with surgical interventions, weakness, and with aging. Dorey, in a 2006 publication, states that "The storage symptoms of frequency, nocturia, urgency and urge urinary incontinence can be treated with pelvic floor muscle exercises, urge-suppression techniques, and behavioral modifications including fluid intake advice." [5].

My pelvic floor work can help you identify these muscles, teach you how to contract them properly, and give you an exercise protocol for improving strength, tone, and function.

3. Referred pain. Referred pain from excess tension in the pelvic floor muscles can be felt in the penis and urethra, resulting in sensations of discomfort, burning, or pain despite there being no evidence of infection. This can be a difficult concept to grasp. In cases of referred pain the source of the problem is not necessarily where the pain is felt. Even though there may be nothing wrong with the penis or urethra, the mind can "report" (i.e. you will feel) that this part of the body is painful. In the absence of infection or other pathology, this pain is most often caused by tight areas, or trigger points, in the pelvic floor. Resolving this muscular tension often resolves the pain. In 2010, Westesson and Shoskes concluded that "A significant ... factor in generating pain in many men with CP/CPPS is pelvic floor spasm. This muscular spasm alone can produce and mimic the pain and LUTS [lower urinary tract symptoms] of CP/CPPS." [6].

My massage and bodywork approach to addressing referred pain is to gently stretch and lengthen the tight muscles responsible for your pain, thereby resolving spasm and tension. This will deactivate the trigger points that create the pain referral and enable these muscles to return to normal tone and function.Back to top

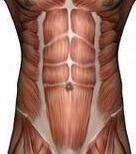

The Role of the Abdominal Muscles

Many medical professionals are unfamiliar with the relationship between the abdominal muscles and urogenital symptoms. Further, men are often unaware of their own abdominal tension, or that this tension may play a role in their symptoms. Irritable, tight, or 'held' abdominal muscles can develop in response to acute or chronic mechanical (physical) overload, difficulties with digestion or elimination, visceral disease (visceral refers to the organs of the abdominal cavity), or emotional stress. Regarding the latter, the abdomen can be particularly sensitive to both mental and emotional stress, including anxiety, worry, fear, anger, or depression. Any of these can result in conscious or subconscious abdominal tension and dysfunction that can refer to the urogenital system and create urinary symptoms and / or genital pain.

Simons et al. state that the abdominal muscles are capable of initiating dysfunctional responses in both the bladder and the urinary sphincters. The result can be "increased irritability and spasm of the detrusor [bladder] and urinary sphincter muscles, producing urinary frequency, retention of urine, and groin pain." [12]. They further state that "Urinary frequency, urinary urgency and 'kidney' pain may be referred from TrPs [trigger points] in the skin of the lower abdomen, as well as from TrPs in the lower abdominal muscles.". Wise and Anderson add that the Pyramidalis, a variable triangular muscle above the pubic bone, "can refer pain and sensation to the bladder, pubic bone and urethra." [13].

The specific areas of the lower abdominal muscles most often involved are found just above the pubic bone centrally, above the inguinal ligament laterally, along the course of the Rectus Abdominis between the navel and the pubic bone, in the External and Internal Obliques on either side of the lower Rectus Abdominis, and sometimes around the navel itself or in the Linea Alba that connects the navel to the pubic bone.

In addition to causing the urinary symptoms described above, the muscles of the lower abdomen can refer pain or discomfort to the groin, the testicles, and the penis.Back to top

______________________________________________________

Several specific topics warrant a brief discussion:

Post-Micturition Dribble (PMD)

This is defined as "when men experience an involuntary loss of urine immediately after they finish passing urine, usually after leaving the toilet. It is neither stress dependent (due to exertion) nor due to bladder dysfunction... The condition can be a nuisance and cause embarrassment." [7]. This is attributed to a "failure of the bulbocavernosus muscle [also called the bulbospongiosus] to evacuate the bulbar portion of the urethra, causing a pooling of urine... which can dribble with movement." [5]. When this condition is present, many men learn to "milk" the urethra by placing the fingers behind the scrotum and massaging the bulbar portion of the urethra in a forwards and upwards direction to encourage a more complete draining of urine. If milking is not sufficient, pads or dribble collectors may be worn.

Because the bulbospongious muscle contracts in tandem with the other pelvic floor muscles, pelvic floor exercises were proposed as an effective treatment for PMD, and research has confirmed the benefit of this approach. In a 1997 study, Paterson and colleagues concluded that "Pelvic floor exercises were more effective in reducing urine loss than urethral milking in this study." [8]. More recently, Dorey had similar results: "...pelvic floor muscle exercises were significantly effective in curing post-micturition dribble and superceded bulbar urethral massage for this condition." [5].Back to top

Post-Radical Prostatectomy

Radical prostatectomy is a surgical operation to remove the prostate gland and some of the tissue around it. It is "the most effective treatment for curing early stage prostate cancer." [9]. This operation, however, "causes many complications, among which urinary incontinence is the most distressing." [10]. Dorey states that "The internal

[urinary] sphincter is damaged in all forms of prostatectomy.", and thereafter continence relies on the strength and integrity of the external urethral sphincter [5].

[urinary] sphincter is damaged in all forms of prostatectomy.", and thereafter continence relies on the strength and integrity of the external urethral sphincter [5].

Too often patients are not empowered to take pre-surgical action to strengthen their pelvic floor, nor are they given exercise guidance post-surgery. In both cases, pelvic floor muscle exercises are an effective tool to minimize the effects of tissue damage and strength loss, and to either better manage their incontinence or facilitate a quicker return to full continence. Floratos and colleagues, in a study that initiated pelvic floor muscle exercises immediately after catheter removal, found that "neither the severity of incontinence initially nor the age of the patient was correlated with treatment outcome... The results were excellent in both groups, giving an objective continence rate at 7 months after surgery of about 90%." [10]. Sighinolfi et al. report that "Pelvic floor muscle exercises seem to result in improved urinary continence and erectile function after radical prostatectomy." They conclude that such exercises "represent an attractive option." [9]. Dorey, in a literature review, concluded that "There is grade II level evidence that pelvic floor muscle exercises seem to have merit as a treatment for post-prostatectomy incontinence. ... This level II evidence showed that early return to urinary continence was found in some men who performed pelvic floor exercises before and after TURP [see below] and before and after radical prostatectomy." [5].Back to top

Transurethral Resection of the Prostate (TURP)

This is "the most frequently performed operation for BPH" [Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia, or an enlarged prostate] [5]. Part of the prostate gland is surgically removed, usually to help relieve moderate to severe urinary symptoms. As with radical prostatectomy, postoperative continence relies on the external sphincter reinforced by the pelvic floor. Likewise, exercises can help manage or resolve urinary continence issues related to TURP.Back to top

Climacturia

As defined above, this condition involves urine leakage during orgasm. It "has received little attention, but it represents a relatively common occurence after radical prostatectomy." write Sighinolfi and colleagues [9]. Their pelvic floor exercise protocol resulted in climacturia being "subjectively reduced in all the subjects". They further state that the mechanisms by which these exercises are thought to work can result in "limiting or even avoiding prostatectomy side effects, including orgasm related incontinence."Back to top

______________________________________________________

Pelvic floor muscle exercises will not be effective for all men, as not all urinary issues are directly related to the pelvic floor. It also takes motivation and a commitment of time. For some, greater strength may help you manage your symptoms better but may not resolve them. It is important to keep in mind however, that there is no downside to exercising the pelvic floor and no negative side effects. A strong pelvic floor has benefits in many other areas such as core support and enhanced sexual function.

References

Books are in bold regular text and journal articles are in bold italic text

[1] Nguyen CT and Shoskes DA. Chronic Prostatitis / Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome. Humana Press, 2008. Shoskes, DA, ed.

[2] Anderson et al. Sexual Dysfunction in Men With Chronic Prostatitis / Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome: Improvement After Trigger Point Release and Paradoxical Relaxation Training. Journal of Urology 2006; 176: 1534-1539.

[3] He W et al. Chronic Prostatitis Presenting With Dysfunctional Voiding and Effects of Pelvic Floor Biofeedback Treatment. BJU International 2010; 105(7): 975-977.

[4] Weiss JM. Pelvic Floor Myofascial Trigger Points: Manual Therapy for Interstitial Cystitis and the Urgency-Frequency Syndrome. Journal of Urology 2001; 166: 2226-2231.

[5] Dorey G. Pelvic Dysfunction in Men: Diagnosis and Treatment of Male Incontinence and Erectile Dysfunction. John Wiley and Sons, Ltd., 2006.

[6] Westesson KE and Shoskes DA. Chronic Prostatitis / Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome and Pelvic Floor Spasm: Can We Diagnose and Treat? Current Urology Reports 2010; 11: 261-264.

[7] Dorey G. Post-micturition Dribble: Aetiology and Treatment. Nursing Times 2008; 104(25): 46-47.

[8] Paterson et al. Pelvic Floor Exercises as a Treatment for Post-micturition Dribble. British Journal of Urology 1997; 79(6): 892-897.

[9] Sighinolfi et al. Potential Effectiveness of Pelvic Floor Rehabilitation Treatment for Postradical Prostatectomy Incontinence, Climacturia, and Erectile Dysfunction: A Case Series. Journal of Sexual Medicine 2009; 6: 3496-3499.

[10] Floratos et al. Biofeedback vs Verbal Feedback as Learning Tools for Pelvic Muscle Exercises in the Early Management of Urinary Incontinence after Radical Prostatectomy. BJU International 2002; 89: 714-719.

[11] Potts JM. Genitourinary Pain and Inflammation: Diagnosis and Management Humana Press, 2008.

[12] Simons et al. Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction: The Trigger Point Manual. Volume 1: Upper Half of the Body, Second Edition. Williams and Wilkins, 1999.

[13] Wise D. and Anderson R. A Headache in the Pelvis: A New Understanding and Treatment for Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndromes. National Center for Pelvic Pain. Revised 6th edition, 2010.